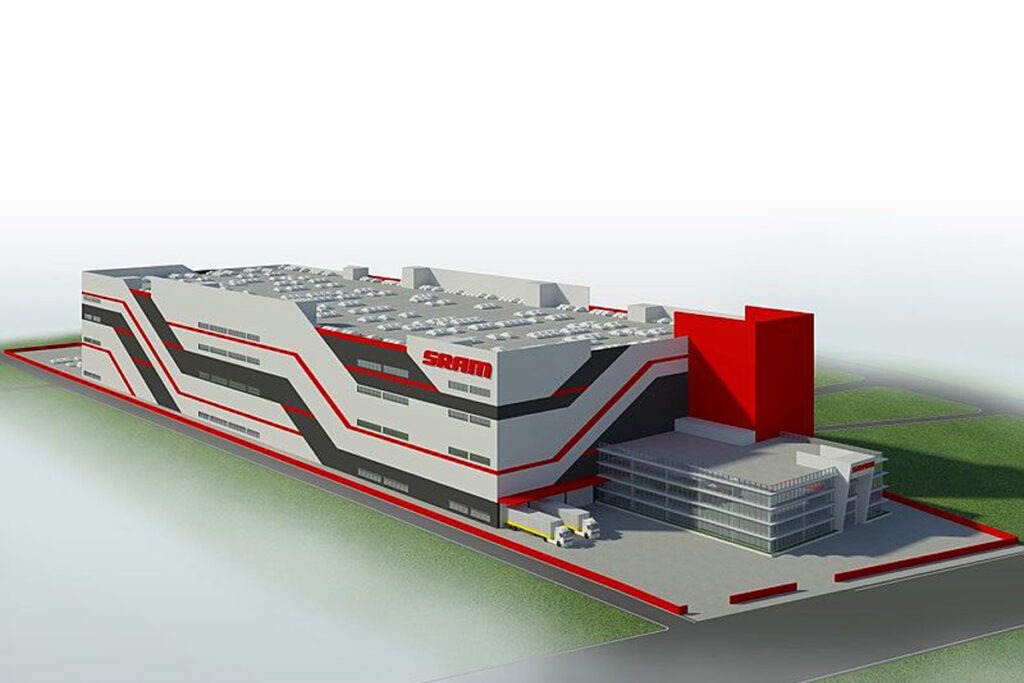

Inside SRAM’s Factory. – New A$800 Million Factory Coming Soon

Taichung District, Taiwan

Taiwan is an island that lies just 180 kilometres off the coast of mainland China. The entire island is barely more than half the size of our smallest state, Tasmania.

Two thirds of Taiwan is covered by extremely rugged mountains, ranging up to almost 4,000 metres high. That’s great for providing some epic mountain biking trails, but means that almost all of Taiwan’s 23.4 million residents are crammed onto a narrow strip of flat land down its west coast, with a total area comparable to greater Sydney or Melbourne.

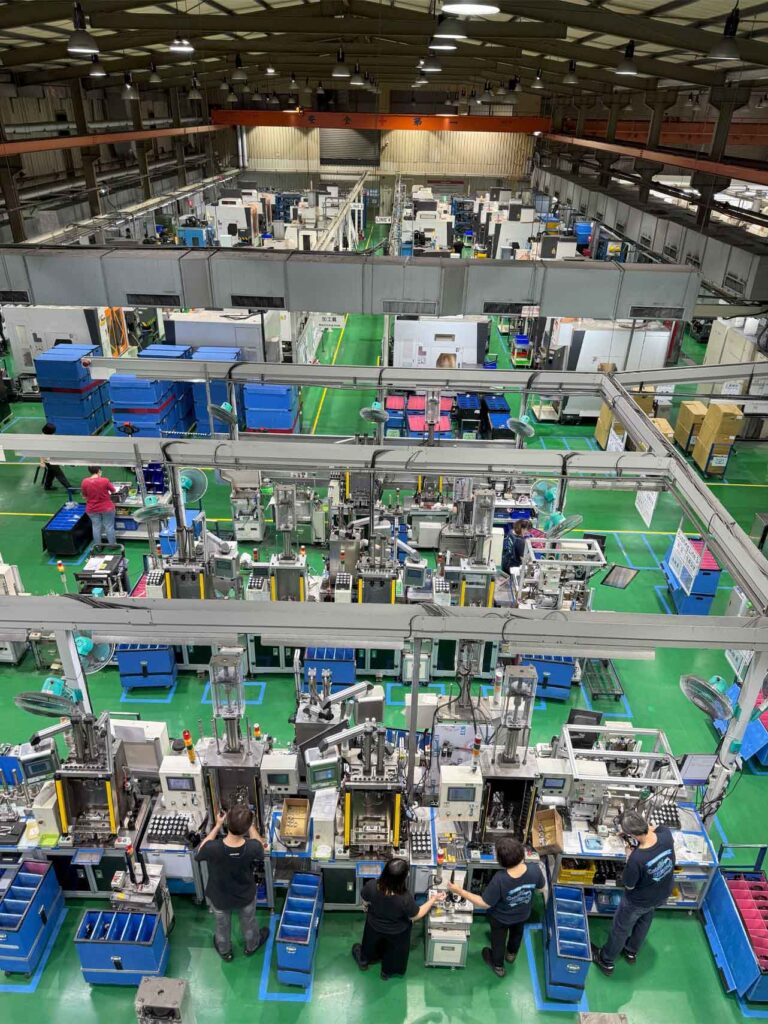

That leads to a density of living and working conditions completely foreign to most westerners. High rise apartments are everywhere and even factories are typically in multi storey buildings.

As SRAM’s current ageing main factory has grown, they’ve added slivers of land and buildings to the point where they’re now renting space from 23 different landlords on their current site!

I’ve visited this factory four times over the past 25 years. It was amazing to see how much things had changed in the eight years since my most recent previous visit.

Our bewildering factory tour took us up and down stairs and through corridors linking one building to another. It could be best described as a “rabbit warren”.

For my previous three tours, I’ve visited as part of a media tour organised by SRAM’s former Vice President of Marketing, Dave Zimberoff. Then we were given more time to ask questions and take photos.

This time I tagged along with three visitors from one of SRAM’s larger bicycle brand OEM (Original Equipment for Manufacture) customers. Our host was Joao Pires, Director of Manufacturing Asia. Originally from Portugal, Joao oversees this and SRAM’s two other factories in Taiwan.

Soon all three sites will be merged into a single building, currently under construction, of over 100,000 square meters, located not far from the factory I toured, which is in the Taichung district of Taiwan – the epicentre of Taiwan’s bicycle industry.

That’s a huge vote of confidence by the American owned SRAM that Taiwan won’t be bombed or invaded by China anytime soon. I’ve found that the Taiwanese are fairly reluctant to discuss this topic. They’ll tell me that they’ve been living with threats for decades and just want to get on with life. When I specifically asked Joao about this “elephant in the room” he stressed that his answer was his personal opinion only. He thought that Japan and South Korea would quickly come to the aid of Taiwan and deter China from trying to invade.

After a mix up with the times resulting in a two hour wait to get started, when I went to take a photo of the first production area we visited, I was horrified when Joao said, “No photos!” Fortunately, I managed to persuade him to relent, with a compromise of just still photos and no videos. Understandably there’s a significant amount of IP (intellectual property) that SRAM doesn’t want to share.

Our tour lasted just over an hour, but compared to the half day or so of previous tours, that made it extremely rushed, with no allowance to set up photos.

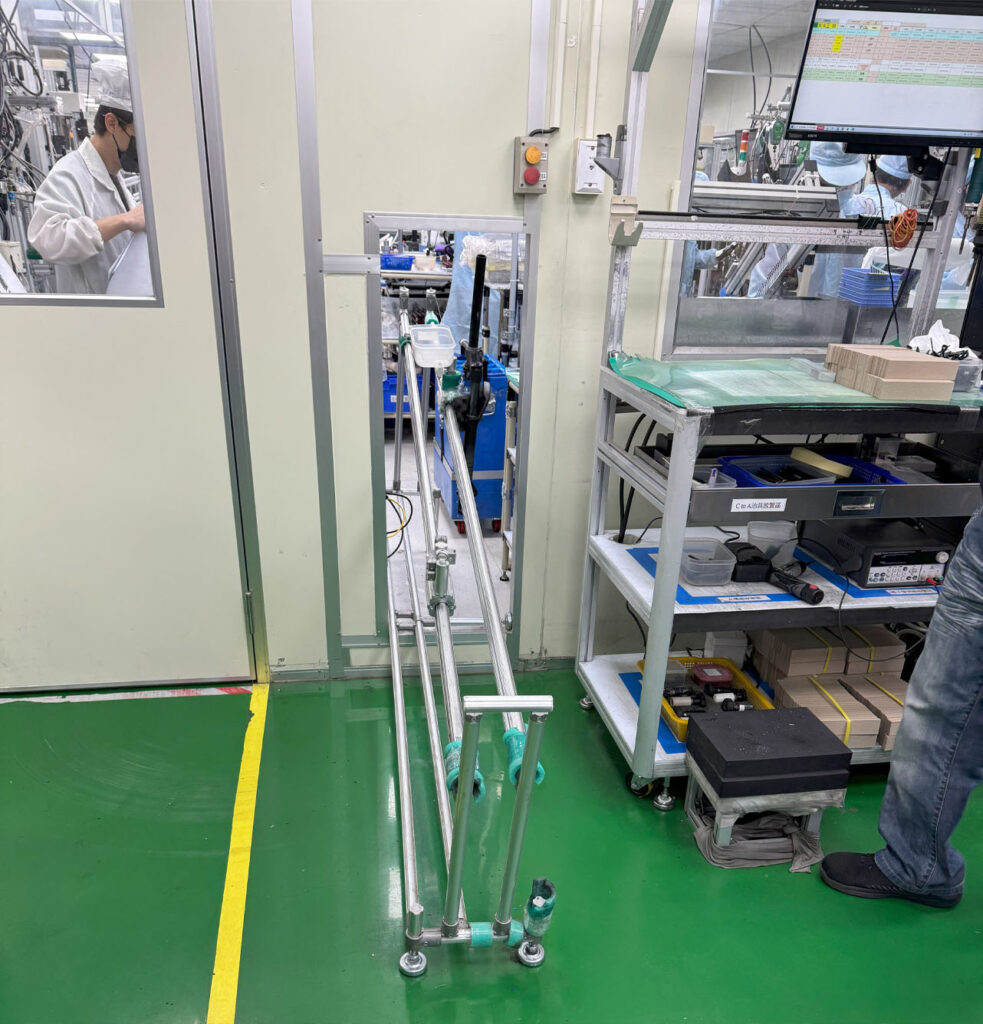

Any production that involves hydraulics or electronics happens inside clean rooms with workers wearing hospital-style clothing and headwear. We were not inside these areas, but I could take photos through windows.

Every resource within SRAM’s factory is used with maximum efficiency, including space, energy, time and materials. Every component is made to order. In other words, they’re not rumbling away making a thousand forks a day and putting them in a warehouse. They might be making 587 specific models of fork for Trek and 313 for Specialized – not a single fork more.

There are separate areas for brakes, derailleurs, rear shocks, forks, dropper posts and so on. Within each of these areas, SRAM design their production lines to be able to make all of their many different models – it’s all about flexibility in responding to customer demand.

SRAM is located in the heart of an intricate web of sub-component suppliers and bike manufacturing customers. It’s a complex ecosystem with delivery trucks coming and going all day.

Joao said that one of their key philosophies is, “Bad news needs to travel fast!”

First thing every morning the workers for each production line meet with their Line Leader to discuss both their planned output for the day, in particular, any current or potential problems. They’re encouraged to speak up because SRAM knows they’re best informed, being closest to the actual work and machines. An hour later, those Line Leaders meet with their Section Leaders. Then the Section Leaders meet with senior management, so that within half a day every day, any serious problems can be communicated all the way to the top.

SRAM says their quality is reliant on optimising the Four M’s – Materials, Machines, Methods and Men. (Clearly “Four M’s” rolls of the tongue better than “MMMW”, because it looked like at least as many women, if not more, work at this factory than men.)

As you will see from the photos in this article, there’s a lot of hand work and very little autonomation at this factory. That’s a deliberate policy to enable more flexible production. Every process at every workstation is analysed. Typically production teams are small, only 15-25 workers. SRAM knows exactly how many workers are required on each production line for a given level of output and what to do if they have one, two or more less on any given day.

SRAM’s factory was a hive of activity. I’ve visited a lot of bike and component factories over the decades across Asia, Europe and America. I still remember my very first visit to a Taiwanese factory – to SunRace in about 1996. I couldn’t believe how fast everyone was working!

I actually snuck away from the media group I was with to go back to the previous room and see if they were just “putting it on” to impress the visitors – they weren’t! I soon discovered that relentless speed, all day every day, is typical and SRAM is no exception.

One critical metric that SRAM is always striving to improve is the time taken to go from raw materials (including sub-components supplied from outside) through to finished components.

That’s because the moment you start manufacturing anything you’re investing space, energy and capital into that partially finished component, that you won’t turn into cash until it’s finished and shipped.

In some cases, this production time has been reduced from two weeks down to just four hours.

It has been tough times in the global bicycle industry since the covid bike boom busted during 2022. Although the factory still looked busy on the day I visited, Joao said they had the capacity to increase output by 50%.

Over the years they’ve consolidated from five Taiwanese factories plus a warehouse to three factories and a smaller warehouse. SRAM used to also manufacture in mainland China but closed that factory in 2017.

“We’re committed to Taiwan,” Joao said. “The supply chain is very close.” But he also revealed that SRAM are expanding their production capabilities in Portugal, where they’ve had a presence for decades after acquiring a chain manufacturer. This is in part because Portugal is within the European Union, therefore avoiding tariffs for that key market during these uncertain times.

If my factory tour to SRAM was anything to go by, there’s still plenty of life left in the bicycle industry. I’m really looking forward to visiting their brand new consolidated factory, which according to Joao, will be opening soon.

Thanks to SRAM for giving me this tour. This visit and article were not sponsored. I travelled to SRAM at my own expense.